When time stopped. Shetland & the Queen of Sweden: A Shetland shipwreck

Cannon from the Queen of Sweden shipwreck, off the Knab, Lerwick. Photo: Donald Jefferies.

Time stood still for me today, as I paused and listened to the wind howl down the chimney. In that moment, I was reminded of something someone told me once, a marine archaeologist, who said that one of the most moving things he had discovered on a shipwreck was a stopped clock, stopped at the precise time of loss. In a world governed by time, a stopped clock holds such profound meaning. This idea, of time standing still forever, is something I think about whenever I consider the wrecks lost at sea here in Shetland.

It got me thinking about men at sea in the past, before modern GPS, and the trepidation they must have felt as a strengthening wind took hold and ripped through the rigging, and the mounting fear as the ship began to roll and pitch. And for the ships sailing on our watery highways, the difficulty navigating these unfamiliar waters must have been a tremendous burden. Despite our apparent remoteness, Shetland sits in the centre of a great nautical crossroads; which opens up the world. It’s little wonder that over the years we have seen our fair share of notable shipwrecks around our rugged coastline.

Renowned for extreme weather and heavy unpredictable seas, many ships have been lost in and around our exposed coastal waters. Of these, only a small handful pre-date 1800. Many ‘ancient wrecks’ simply don’t survive. They are broken up and carried away by the sea, great rafts of flotsam ready to be washed up on the beach, a gift from the sea to the opportunistic beachcomber.

Whatever their fates, those vessels which do survive are of even greater importance to our understanding of life at sea and the societies who took to the oceans. These rare, historic wreck sites are precious time-capsules – snapshots capturing every aspect of life at the exact time of loss – the moment that, for those on board, time stopped. They provide valuable information to archaeologists, historians, storytellers or curious individuals like me about the ship; including fittings and armaments, the cargo and the personal possessions of the crew on board. They tell us how they lived, and fought, how they worked and what they ate.

Alex Hildred, a diver on the famous Mary Rose, sums up historic wreck sites very well, she says that they offer a unique form of archaeological site: ‘It is a home, it is a community, it is a workplace, and it is a fighting machine’.

What this gives us is every aspect of life, a beautifully encapsulated snapshot of time. A window into the past.

Today we are still hobby beachcombers here in Shetland (and you can read more about that here), our inner treasure-hunters scouring the tideline in the hope that something more dazzling than a discarded boot will have found its way onto our beach and into our expectant hands. In the past, these wrecks provided islanders with vital supplies – wood for roofing, for furniture, for agricultural tools and children’s toys. Or, wrecks were targeted by divers salvaging finds – treasure hunting and looking to make a quick buck. My great-great-grandfather, one of the many islanders whose fate was surrendered to the sea, lost to the waves while gathering wood from a wreck. (I wrote his story here.)

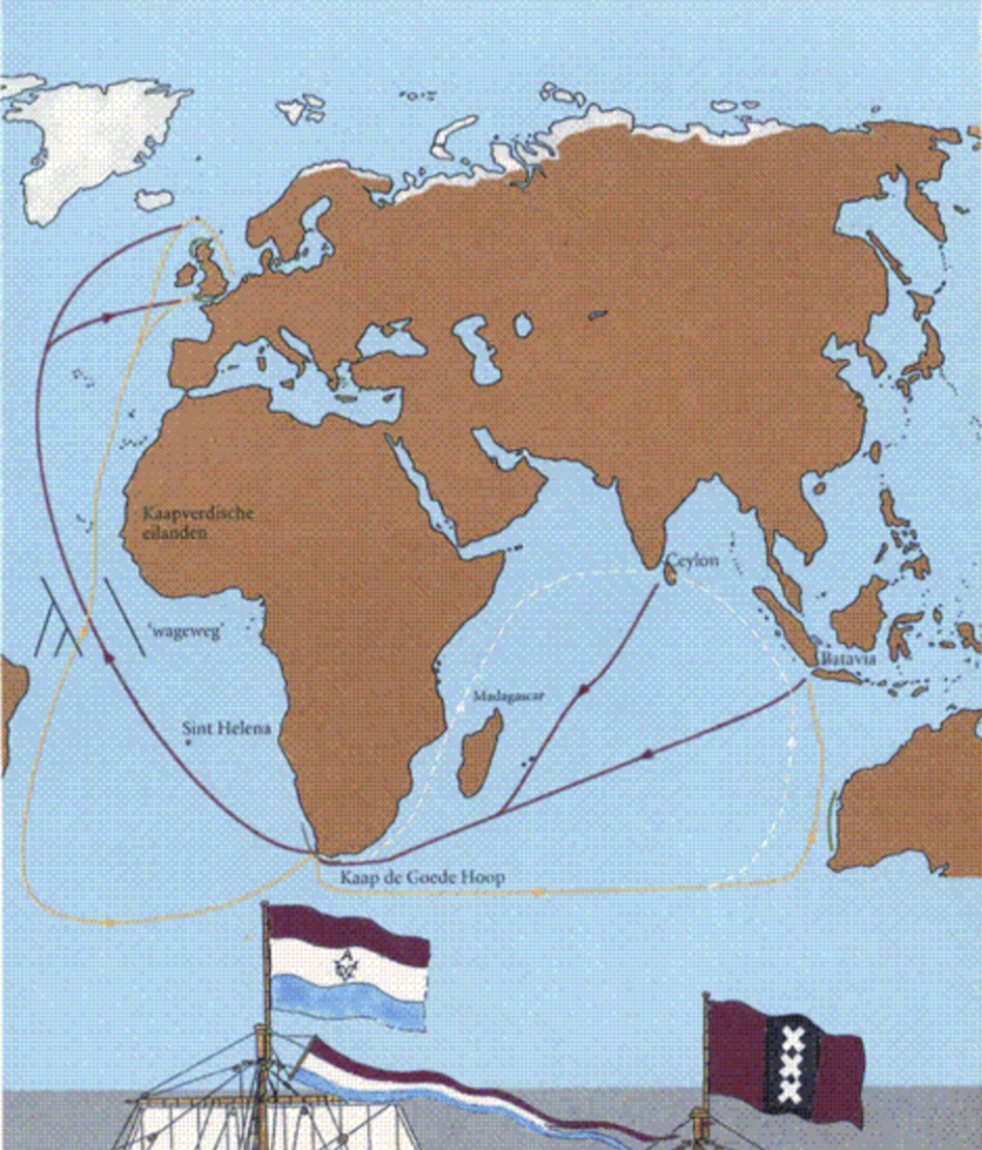

And to give a little context, Shetland has (perhaps surprisingly been) a major trade route all over the world from North America and Scandinavia to the East Indies and Australia and every conceivable place in between – and it has been so since the first explorers (in our case, the Vikings, who plied the oceans from the 9th century) arrived. During the 17th & 18th centuries ships often chose the northern route around Shetland to avoid conflict (or full-scale war) in the English Channel – meaning that more and more vessels found their journeys taking them into Shetland waters. I wrote more about the East Indie connection here.

Navigating around unfamiliar Shetland waters was a challenge in the 18th century. This chart and navigation tools demonstrate what would have been available to the crew on the Queen of Sweden as she approached Shetland waters. Note the outline of hills on the chart - this was done so that the crew could recognise which part of the land they might be approaching from the shape of the hills. These items are all held in Shetland Museum & Archives. Photo: Davy Cooper

Shetland & the Queen of Sweden

One of these incredible historic vessels, the flagship of the Swedish East India Company, was the Drottningen af Swerige (translated as Queen of Sweden). Under the command of Captain Carl Johan Treutiger, the Queen, a 147ft, 950-ton merchantman, carried 130 men and 32 guns. Built in Stockholm in 1741 for the princely sum of £12,500 she was the largest vessel in the company’s fleet. A trading vessel to China for the Swedish East India Company she was a ship to admire and marvel over – and one they were rightly proud of.

She was partially loaded, en route to Cadiz (Spain) for more supplies before continuing to Canton (China) when she floundered here.

Sailing with the Stockholm, both ships left Gothenburg, on Sweden’s western seaboard, on 9th January 1745, on ‘a day of chill easterly wind and white driving sea fog’. After making good headway, the weather deteriorated as they neared Shetland. With high winds, blizzard conditions and poor visibility, the ships struggled to maintain course. The Stockholm floundered and was lost off Braefield, Dunrossness (in Shetland’s south mainland) on 12th January at 5pm. The Queen continued, her Captain deciding to run for the safety of Bressay Sound (Lerwick). As she came into sight of the harbour entrance and safety, the weather closed in and visibility was again lost to a wintery shower. At around 9pm she struck a rock at the Knab (pictured) and was lost in only 10 fathoms of water. The crew from both ships survived, but the vessels were lost to the sea forever.

An unlikely trade with the East

Although this trade to the east seems an unlikely one to have influenced Shetland, it was common and in fact, necessary! The English Channel during the 18th century was not a good place to be – privateers lay-in-waiting, ready to attack unsuspecting ships, plundering cargoes. These cumbersome merchantmen, such as the Queen, were difficult to navigate – especially within the tight and crowded confines of the busy Channel. So, that is why so many of them found themselves taking the longer, ‘safer’ northern route, around Shetland – risking both ship and men in our northern waters. And in fact, around 25 of these great ships were lost here, and this, I find incredible. (I wrote about a few of these here) That these elegant trading ships with billowing sails and ornately decorated hulls would find themselves in our waters – a corner of the UK forgotten and ‘boxed-off’ by geographers – is testament to the strategic importance of our island archipelago which sits on this nautical crossroads where the North Sea and North Atlantic meet in a dramatic clash of power and motion. A braver me would pull on a wetsuit and head down to the murky depths exploring. But I’m not a braver me so I’ll tell this story from dry-land.

Just as today we are a nation, and world obsessed with travel, so too were the men of the 18th century. People wanted to stand out in society and the pull of the east was great. Middle and upper-class social circles craved ‘exotic’ items brought back, and porcelain such as this photographed, from the Queen, was highly sought after. Extensively excavated, the finds from the Queen can tell us a wealth of stories about society at the time.

Small finds from the Queen of Sweden. These are now held in Shetland Museum & Archives. Photo: Davy Cooper

The Queen beneath the waves

The personal finds, carefully excavated and brought back to the surface, particularly moved me, collected from the seabed hundreds of years after they were lost to time in a moment of panic, fear and confusion. A small signet ring. A trade item perhaps? We don’t know. It could have as easily been a marriage band, an heirloom a gift. If we think about our personal possessions and how we come to cherish them, then the bone comb could just have easily been a birthday present from a dearly-departed loved one, it may have been the only memory for a sailor of a wife back at home. We don’t know. All we know is that there were buttons and buckles, accessories and shoes. All these personal finds, belonging to a member of the ship’s crew on that fateful day and each with a story to tell.

Much of the ship's fittings were sold at auction at the time of wreckage but some have made it into the collections at Shetland Museum & Archives

We know a lot about the finds from the Queen – some of the cargo was salvaged at the time of wrecking and sold at auction. The finds were listed and the auction catalogue is now held in the Shetland Archives. These salvaged parts included; ropes, sails, oak planking, muskets, pistols and bayonets, tar barrels, candles, linseed oil, vinegar, soap and lead, as well as the ship’s rudder and wheel.

The wreck was re-discovered in October 1979 and excavated by marine salvor, Jean-Claude Joffre. The collection, containing almost 500 individual items offer a tantalising insight into the life and workings of an 18th-century trading vessel.

Protection

One reason for highlighting the Queen in this blog post (other than the fact I love shipwrecks) is because a consultation has recently been launched by Historic Environment Scotland (HES) to recognise and protect this important site which is thought to be the best example of a Swedish East Indie merchant ship in Scottish waters. HES, who advise Scottish government on the designation of historic Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), has recommended the Scottish government recognise and protect this important part of Scotland’s marine heritage with HMPA status.

Historic wreck sites such as these are protected and safeguarded through various legislative acts – Protection of Wrecks Act (1973); Zetland County Council Act (1974) and the Marine (Scotland) Act (2010) to ensure that they are safeguarded against ‘inadvertent or deliberate damage’. Diving on a site protected by this act is prohibited unless a license through HES is sought.

Evidence of the Queen can still be viewed on the seabed, including her impressive cannons, the crew all made it back home to their families safely, and for those of us who dive today - we're asked to take only photographs, and leave only bubbles.

With love (and bubbles),